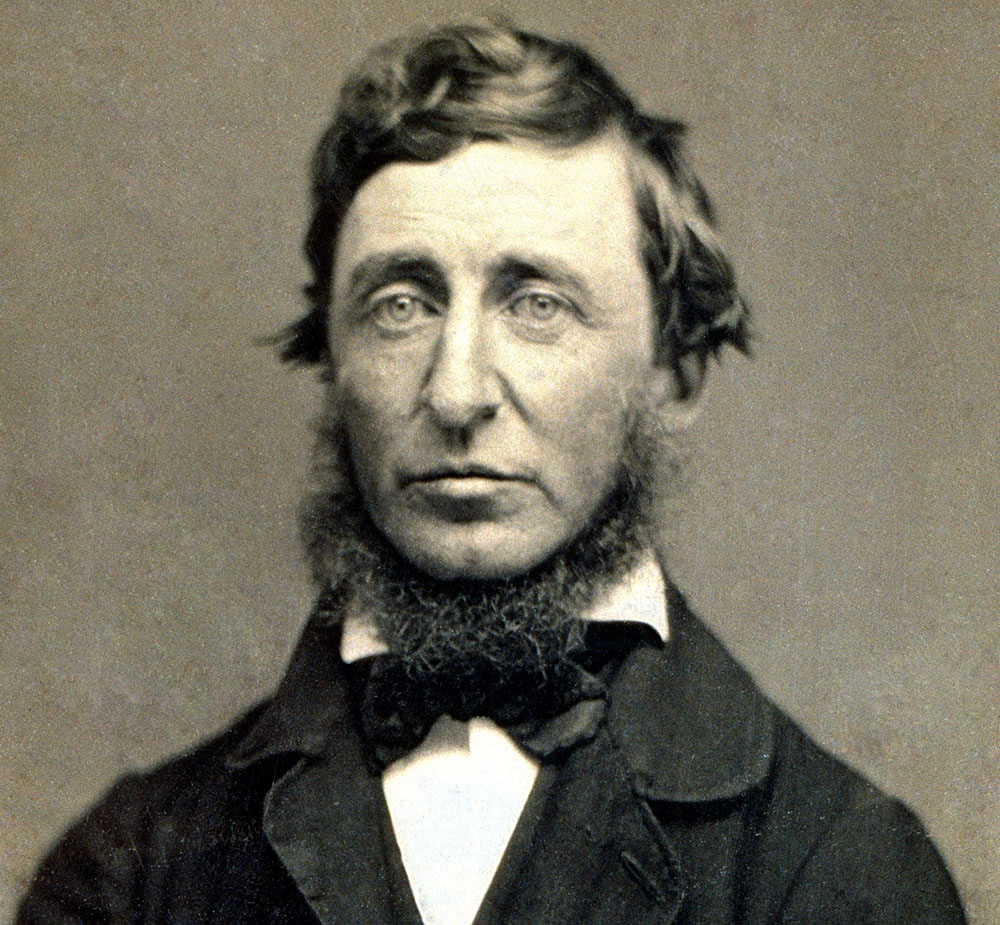

A true pioneer in the mid-19th century, Thoreau was the first American to articulate the value of the pure natural world. An influential writer, his words resonated with opinion leaders and the general public alike and laid the foundation for the explosion of conservation policy that began a generation later.

Before Thoreau, there was no conservation because there was no perceived need for it. Bringing full civilization to the new nation was just a matter of taming nature, and America seemed inexhaustible in its vastness.

In 1845, he moved to a small house on Walden Pond, about two miles outside of Concord, Massachusetts. “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to confront only the essential facts of life…. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.” In 1854, he published Walden, or A Life in the Woods, in which he recounted his two years at the pond and reflected on the value of living a simple life in nature. This reflected the core philosophy of Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, the other principal figure in the transcendentalism movement, based on the belief that pure nature held transcendent truths.

Thoreau’s most powerful and enduring summons was “Walking,” delivered as a public lecture in 1851 and published, after his death, twelve years later in the Atlantic Monthly. He began by arguing that “The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the world.” He used the word “Wildness,” rather than “wilderness” because he had two notions in mind, the wildness in nature and the wildness—the creativity and bravery—that exists within humans. His conclusion in “Walking” shows how the two meanings of wildness can wrap together: ”In short, all good things are wild and free. There is something in a strain of music, whether produced by an instrument or a human voice,--take the sound of a bugle on a summer night, for instance--, which by its wildness…reminds me of the cries emitted by wild beasts in their native forests.”

Thoreau did not experience anything close to John Muir’s total immersion in the natural world, but he had a broad audience for his bold ideas. American conservation owes much to Thoreau’s trailblazing work, which was one of the influences that led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, the first national park in the world and, generally, to the conservation explosion of the early 20th century embodied by TR. And his clarity and unwavering insistence continue to inspire us today.

America’s Top 10 Conservation Heroes is a series honoring the individuals and organizations that have made the biggest mark on conservation, environmental protection, and awareness of the outdoors. The series is written by Charles Wilkinson, Distinguished Professor at the University of Colorado and author of fourteen books on law, history, and society in the American West.

Header Photo: Walden Pond and a replica of Thoreau's cabin (Flickr credit: Ptwo)

America’s Top 10 Conservation Heroes

1. Theodore Roosevelt

2. John Muir

3. Rachel Carson

4. Stewart Udall

5. Aldo Leopold

6. Ansel Adams

7. Earthjustice

8. Henry David Thoreau

9. Edward Abbey

10. Bruce Babbitt