John Muir, honored scientist, outdoorsman extraordinaire, influential writer, and passionate, irrepressible activist, changed the world in ways that continue to make our lives better and richer a century later.

Muir, a child prodigy who won blue ribbons for his inventions at the Wisconsin State Fair, studied botany and other subjects at the University of Wisconsin for three years but the indoors could not hold him. He and his brother ventured up to Canada to explore the woods of Ontario. Then, in 1868 at the age of 29, having just finished a 1,000-mile hike from Indiana to Florida, he stepped off a steamship onto the San Francisco wharf and asked directions to “any place that is wild.” He went straight to the Sierra Nevada, which captured his imagination upon his first visit:

“Then it seemed to me that the Sierra should be called, not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light. And after ten years of wandering and wondering in the heart of it, rejoicing in its glorious floods of light, the white beams of the morning streaming through the passes, the noonday radiance on the crystal rocks, the flush of the alpenglow, and the irised spray of countless waterfalls, it still seems above all others the Range of Light.”

He immersed himself in the Sierra Nevada, which he loved so, building a base of knowledge through years of hikes of 20-40 miles a day. Muir proved, contrary to the views of Josiah Whitney, the giant of California geology, that Yosemite Valley and its environs had been crafted by glaciers. He understood the yet unnamed science of ecology—“ We all travel the Milky Way together, trees and men,” “Everything is bound fast by a thousand invisible cords”—and generations later was made a charter inductee into the Ecology Hall of Fame.

Although he had not planned on it, Muir became a prodigious writer (his Collected Works filled up ten volumes). By the early 1880s, his evocative articles and books, drawn from his vigorous treks in Yosemite and north to Alaska and south to the Grand Canyon, drew a large and enthusiastic national audience. His adventures, such as one in a violent high Sierra windstorm when he chose to climb to the top of a fir tree 100 feet tall, were hard to resist:

“Never before did I enjoy so noble an exhilaration of motion. The slender tops fairly flapped and swished in the passionate torrent, bending and swirling backward and forward, round and round, tracing indescribably combinations of vertical and horizontal curves, while I clung with muscles firm braced, like a bobolink on a reed... I was … safe, free to take the wind into my pulses and enjoy the excited forest from my superb outlook.”

Muir’s readers enjoyed his writing as literature, but he also was whipping up support for conservation. He made wilderness exciting and an object of great worth. At the same time, the land—including his beloved Sierra—was suffering from insults such as logging of giant redwoods and excessive grazing of sheep, which he called “hoofed locusts.”

In 1889, Muir invited an easterner, Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century magazine, out to Yosemite for a visit. Muir showed him the glories and wounds of the Yosemite country and explained that Congress had given it to the State of California in 1864 but that the state was not protecting the land. Congress should take it back. Underwood agreed, and Muir wrote articles urging protection of Yosemite for Johnson’s magazine and newspapers. Within a year Congress created Yosemite National Park.

The 1890 Yosemite statute was an historic moment. In 1872 Congress had designated Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in world history (western writer Wallace Stegner has called our national parks “the best idea we ever had” and today every country has national parks). But, as of 1890, Yellowstone still stood alone. The creation of Yosemite reinvigorated the park idea and many more were established in the years to come. Rightly called “the Father of the National Parks,” Muir’s words and actions led to the creation of Grand Canyon, Sequoia, Petrified Forest, Rainier, Glacier Bay, and others.

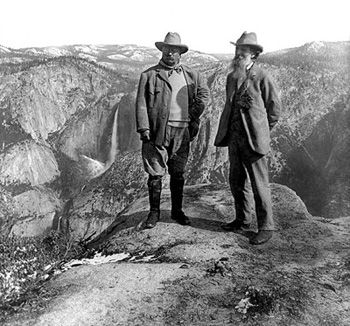

President Theodore Roosevelt knew Muir’s writing and career well and wanted to meet him on a trip to the West in 1903. Knowing of TR’s love of the outdoors, Muir was enthusiastic about it as well (as compared to the earlier visit from Ralph Waldo Emerson, whom he judged to be an “indoor philosopher”). They went in to Glacier Point, as TR reported it, with ”a couple of packers and two mules to carry our tent, bedding, and food for a three day trip.” The two men broke off from the packers and slept under the stars. The President was rhapsodic: “The first night was clear, and we lay down in the darkening aisles of the great Sequoia grove. The majestic trunks, beautiful in color and in symmetry, rose round us like the pillars of a mightier cathedral than ever was conceived even by the fervor of the Middle Ages.”

Muir wanted TR to see the magnificence of the place but also “to do some forest good in talking freely around the campfire." He had three agenda items. At the time presidents had power to designate national forests and put them beyond the reach of the timber barons. Roosevelt already had declared some national forests but Muir believed there should be many more:

“Any fool can destroy trees. They cannot run away; and if they could, they would still be destroyed, chased and hunted down as long as fun or a dollar could be got out of their bark hides, branching horns, or magnificent bole backbones. Few that fell trees plant them; nor would planting avail much towards getting back anything like the noble primeval forests. … God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand straining, leveling tempests and floods, but he cannot save them from fools — only Uncle Sam can do that.”

Muir also wanted have Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove returned to the United States and placed in the Park (in the bargaining over the 1890 statute creating the Park, California had agreed only to have the high country included in the Park). Finally, he urged TR to visit the Grand Canyon and have it protected. All three of Muir’s objectives came to pass as a result of this literally unique lobbying session.

John Muir grieved at the setback that came near the end of his life. San Francisco, seeking to expand its water supplies, pressed for a storage reservoir in the Sierra. The landscape to be inundated was Hetch Hetchy, a magnificent valley just to the the north of Yosemite and often referred to as Yosemite’s “sister valley.” The Sierra Club, founded by Muir in 1892, furiously opposed the project for ten years and generated significant public support. Nonetheless, in 1913 the Raker Act allowed the flooding to go ahead. Muir passed away the next year at the age of 76. Some of his friends and colleagues believed he died of sorrow or a broken heart over the loss of Hetch Hetchy.

In 1916, Congress passed the National Park Service Act, long the dream of John Muir. The statute established the National Park Service as a professional land management agency and enacted a comprehensive mission for the parks, which previously had operated independently and often haphazardly. The Park Service’s mission for these landscapes—“the Nation’s crown jewels”—is to “leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations,” a standard that surely reflects and honors the life journey of The Father of the National Parks.

America’s Top 10 Conservation Heroes is a series honoring the individuals and organizations that have made the biggest mark on conservation, environmental protection, and awareness of the outdoors. The series is written by Charles Wilkinson, Distinguished Professor at the University of Colorado and author of fourteen books on law, history, and society in the American West.

America’s Top 10 Conservation Heroes

1. Theodore Roosevelt

2. John Muir

3. Rachel Carson

4. Stewart Udall

5. Aldo Leopold

6. Ansel Adams

7. Earthjustice

8. Henry David Thoreau

9. Edward Abbey

10. Bruce Babbitt