We wake at 6am to the faint jingle of Lorna’s watch muffled by her sleeping bag. My body creaks as I pull my sore arms from my sides, grab my headlamp, and light the JetBoil that I had carefully placed outside our tent the night before. Dawn is just beginning to creep across the sky, slowly dimming the stars and dampening the pain of our early start. The air is calm but startlingly cold—just as the meteogram had predicted—and my breath spins small clouds that mimic the steam now rising from the stove..jpg)

I glimpse up at Aguja de L’S, the rightmost peak in a skyline dominated by Cerro Fitz Roy to its left. A thin smear of ice glazes the west face. It’s February—our version of “August” in the southern hemisphere—but it’s been a cold summer. The ephemeral ice route was given the fitting name Jugo de Hielo: “Ice Juice.” Even now, in my morning haze, the phrase sends my thoughts to Domo Blanco, an artisan ice cream shop just a stone’s throw down valley in El Chaltén. Perhaps today we’ll earn ourselves a few more Domo points, I think, referring to the imaginary reward system gringo climbers have invented whereby feats in the mountains—from summiting a peak to establishing a first ascent—earn varying servings of ice cream upon return to town. I glimpse over at my dwindling food pile: a selection of bars for today, a freeze-dried meal for tonight, a small bag of nuts reserved for the following morning. It’ll be a hungry walk out, and I know nothing—not even Domo points—will stop me from consuming beer and empanadas once we make it back down into town..jpg)

Lorna, a nurse back in our hometown of Bend, Oregon, is no stranger to early mornings. She’s out of the tent before I’ve even sat up, putting the finishing touches on her backpack for the day’s climb. The clanging of metal carabiners invades the single wall of the tent—morning music, alpine-style. I met Lorna just a few months earlier while climbing at Smith Rock, a world-class crag outside of Bend. We’d climbed together throughout the fall and winter, but this trip marked our first time sharing a rope in big mountains. In reality, this was quite the gamble. Although, based on our climbing resumes, complimentary skills, and burgeoning friendship, we suspected we’d make a good pair. Besides, all-female teams are rare in mountains like these, so we weren’t about to pass up the opportunity.

Coffee consumed and bags packed, we begin our approach up the moraine, pausing first to pile rocks over our collapsed tent. The winds in Patagonia are notorious for ripping apart calm skies and taking off with thoughtlessly placed gear, so we do all we can to cover our bases. Just the day before, we’d met Casper here in Nipinino—the climber’s camp nestled on the ridge in the Torre Valley—who’d returned to the base of a climb to discover one boot and his entire backpack missing. It’d been a long walk back to camp in his snug climbing slipper, and we’d found him at a friend’s tent, bartering sleeves of cookies for a spare pair of approach shoes. .jpg)

The moraine leads Lorna and me to the base of a wide and flat-topped peak, aptly named El Mocho. We’d set our sights small this time. With big storms preceding the calm but cold temperatures, we suspected that rock routes would be riddled with snow and ice. “No one’s putting on climbing shoes this window,” our friend Colin had predicted back in town—a voice of reason, given that he’s logged over a dozen seasons in Chaltén. Lorna and I didn’t come to Patagonia prepared to ice or mixed climb, so we decided on a pair of east and north-facing routes (in the southern hemisphere, north-facing faces get all-day sun) on low-lying peaks, in hopes of dry rock. Our tactics had paid off..jpg)

Despite our preparation and luck, predicting conditions in the Chaltén massif is often like playing roulette. No webcams broadcast the mountain conditions, and weather models (which we checked incessantly before departing town) predict varying degrees of wind and rain. The weather seems to unexpectedly thwart the efforts of even the most experienced in the range from time to time. And so we go to the mountains with open minds, Plans A to F, and (hopefully) a toolbox of alpine skills. Forget the ability to free climb 5.14—logistics, adaptability, and efficiency are some of the fundamental skills of climbing in Patagonia.

We nail the approach to El Mocho, having traveled similar terrain a few days prior to reach the nearby Media Luna. At the base of our route, we meet two young Argentine climbers and exchange friendly, excited words in stilted Spanglish. We decide to set off on different variations of the same 400-meter climb, giving the other team space to move at their own pace. By now, the sun’s rays have stretched over the towering Fitz Roy Massif, and Lorna and I shed our jackets and apply another layer of zinc to our faces. We set off and spend the day swapping leads up the immaculate granite buttress. The warm rock and calm air make it hard to believe this is alpine climbing..jpg)

Midway through the climb, a group of Andean condors joins us. They float and dive, riding thermals that spin just off the east face of El Mocho. Two become three, then four, and five. For an hour, the seven of us are playful comrades, defying gravity in our mountain jungle gym. I belay Lorna up to my human-sized perch on top of a pillar and we stare, completely mesmerized by the giant birds. By weight and wingspan, they are the largest in the world. We pause to take it all in, and I file the moment away as one of the most stunning of my short life.

The two of us rappel the route and are down before dark, stopping briefly to chat with our friends Sam and Emma in their bivy cave just a hundred meters from our tent. They had found snow and ice on their route, a south-facing crack-system-turned-gutter. They’d been just a few hundred meters from our sunny foray on dry rock, but cold hands, wet feet, and icy conditions had kept the duo from summiting. Call it luck, or logistics, or maybe a bit of both, but I certainly feel fortunate. Once at our tent—water boiled and freeze-dried meals consumed—Lorna and I slip into our sleeping bags and set another early alarm. The last weather forecast we’d seen before leaving town four days ago had been relatively clear. The following morning should bring heavy winds and a closing of the weather window. We would want to be out of the mountains sooner rather than later..jpg)

In the morning, we rise without hesitation, motivated as much by the prospect of showers and empanadas as by the wind-blown Lenticulars swiftly approaching from the west. Just days ago, we eagerly swapped life in town for the extremes of the mountains; now, the allure of El Chaltén trumps all else. Is it impossible to feel content? No, I think, but these extremes are indeed the spice of the climbing life. And yet as strong as the push and pull may be, we can only move so quickly. Before us sits a dry glacier, challenging route-finding across a moraine, boulder-hopping along an exposed lakeshore, and finally six miles of mindless plodding on a hiker’s trail. Though less than 10 miles total, the tricky terrain requires at least a five-hour slog for even the fittest of climbers. As it turns out, everything in Argentina—from buying a bus ticket to grabbing dinner to, in this case, walking 10 miles—takes longer than you’d think.

Just 45 minutes into our descent from Niponino, the wind picks up—right on schedule with the days-old forecast. I let it propel me forward. I’m racing now, my legs invigorated by the threat of impending doom. Unexpected gusts push from behind, and one particularly strong blow causes me to drop to my knees as I cover my head with my hands. Small rocks and dust careen around me like tiny missiles. I stay tucked long after the gust is gone, my head hanging low. I squeeze my eyes shut, and try to convince myself we’re closer to town than we are.

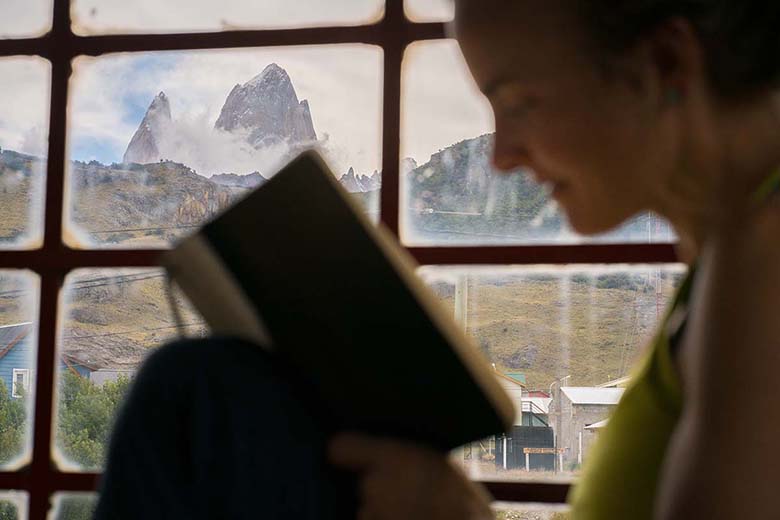

Just a few miles away, wind batters the large, single-paned windows in the upstairs room of the Chocolatería. Long rays of light sneak through, warming the small loft and casting crisscross patterns onto the wide, wooden table. Light bulbs dangle from pitons wedged into cracks in the exposed roof, and an old pair of crampons hangs from the wall behind me. Spirited Argentine music filters from downstairs, rising up like hot air to join the alfajor, steaming coffee, and journal on the table. I gaze outside just as a powerful gust throws nearby trees into chaotic spasms. I relax my back against the long bench and gaze towards the skyline: St. Exupéry, Poincenot, Fitz Roy, Val Biois, Mermoz, Guillaumet. I count off the peaks I’ve climbed throughout my two seasons in the range and I dream of standing atop the others.

Back in my current reality, I rise from my tucked position. The noise in the sky is now hectic: like a busy subway station or loud concert. I can’t think. Around the lake, whitecaps and waves crash on shore, covering my feet in glacial surf. Gusts intensify in force by the minute, slight whispers crescendoing to charging freight trains. I’ve heard some veterans of the range talk about the wind as meditative, about learning to battle with it rather than against it. Right now, I simply find it overwhelming. I yell to Lorna, “This might not be fun, but at least we know we’re fully alive!” My words are muffled by the gale the moment they leave my mouth..jpg)

We reconvene in the woods, where there’s no doubt as to how the windblown Lenga trees have earned their tilt. At this point, silence and calm seem like foreign concepts. Passing the three-kilometer sign, I leave Lorna and run the rest of the way to town, painfully hungry and impatient to finish this mindless portion of our descent. Ahead, smoothies from Chaltén’s hippy vegan restaurant, Curcuma, and fresh empanadas from Tierra de Nadie await (“better than any other empanada in town by an order of magnitude,” as my friend Matt described them). At a small trailer kiosko near the trailhead, I stop for a sleeve of cookies, finishing the entire package in the time it takes me to hike the ¼-mile to the empanada shop. In the Chaltén cycle of feast and famine, our mountain binge is quickly transforming into a different sort of indulgence.

Lorna finds me outside Curcuma, already starting in on the empanadas. Soon, Casper sulks by with his partner, a pair of mismatched shoes on his feet. The duo joins us for smoothies and, as is typical in Chaltén, the conversation immediately turns to the weather. I pull out my phone and log onto the Wi-Fi to check the latest predictions. Now, just minutes after being propelled from the mountains by a lust for fresh food and comfort, we’re sipping on smoothies and planning our next escape. Wash, rinse, repeat. The forecast shows a weather window five days ahead. I notice myself breathing a sigh of relief. For now: rest..jpg)

Throughout the afternoon, climbers slowly stumble back into town, trickling in from the Torre Valley to the west and Piedra Negra in the north. In the afternoon, we begin to gather on the porch of Fresco Bar, the town’s de facto watering hole for both Argentine and visiting climbers, and one of the only establishments that serves up IPAs (pronounced by the locals as “ee-pas”) actually worth drinking. Pints are passed around, alongside glory stories of peaks summited and plans thwarted, of high winds and iced-up cracks. My friends Austin and Nathan climbed a snow and ice route on Aguja Poincenot, which was Austin’s seventh summit of the seven peaks in the Fitz Roy skyline. Salud, we cheers to that. I buy beers for Bruce and Chris, a Boulder-based team who shared the route on El Mocho with us just the day before. A pair of Yosemite climbers—adept on rock, but strangers to true mountain environments—share their tale of being stymied by steep snow on the approach to one of the lower summits.

We flock to the lawn for a game of hacky sack. Gusts come and go, but overall, the wind in town is a far cry from what’s currently raging in the mountains. We take bets on when John and Tad will return from their mission to the west side of the Torres, guessing that wind forced them to bail off the backside and take the long way out—a 24-hour death march across the Marconi Glacier back to town. Just as the bell rings signaling the last call of happy hour, Will and Chris, a pair of Canadian climbers, stumble into our jovial circle, clearly fresh off the trail. Their faces are red with windburn and tired gaits slow their steps.

Every year, climbers from all over the world venture to El Chaltén to gamble with the weather and hope for a chance to stand atop a coveted Patagonian summit. The tiny, colorful town in southern Argentina has become especially popular with a contingent of American climbers, some of whom come back season after season. Writers and photographers, riggers, guides, and seasonal workers make up the vast majority of “professional dirtbags” that can spare weeks—and even months—in an isolated town with painfully-slow internet. Others, like social workers, nurses, business owners, and lawyers, come with two weeks of vacation time hoping to catch a break in the weather.

Climbers have been scaling peaks in the Chaltén massif since the 1950s, but not until the beginning of the 21st century did the range gain enormous popularity as a climbing destination. The advent of weather forecasting in the area—and the unrelated development of the border town of El Chaltén—has played a huge role making the range more accessible. Just 15 years ago, climbers weathered weeks of violent wind in tents on the glaciers, staged to venture upwards once the skies calmed. Now, we rent apartments in town, boulder and sport climb in between empanadas and IPAs, and wait for the meteogram on our phones to tell us when it’s time to go. Previously reserved for alpine hardmen and women, Chaltén is now on the map as a destination even for everyday climbers..jpg)

As the reunion at Fresco gains momentum, I slip away in search of sleep. I cherish the sweetness of these transition times, when comfort and rest feel rightfully earned. The sting of wind is still fresh on my face; the discomfort of an ultralight bag and half-inflated pad are all I know. Early mornings and non-stop days, swollen fingertips, stuck ropes, logistical doubts, fear and loose rock and cold feet fill my recent memories. Now that my hunger is satiated, my nerves are slowing. In my apartment above the local panaderia, the thin, moldy walls seem luxurious compared to the flapping, caving nylon of my tent. I lay my head down on my soft pillow and breathe a breath of contentedness. Right now, the world requires nothing of me but a long night and lingering morning of deep sleep.

Tomorrow, the mountains will already be a distant memory. I’ll rise from bed, my stiff legs providing a gentle reminder of the previous day’s slog. Already, a golden hued lining will begin to wrap itself around our mountain foray—the tumultuous hike remembered as an epic battle rather than a grueling sufferfest. I’ll boil water for coffee, check the weather, and start in on a crossword. Lorna will come join me at the kitchen table, letting out a contented sigh as she sits. And then, with warm beverages and fresh bread from the bakery in hand, we’ll crack open the guidebook and start making plans for the next time..jpg)

Climbing in the Chaltén massif certainly isn’t for everyone, but trekkers will love the town of El Chaltén for its extensive trail system and proximity to stunning skylines. In fact, the tiny mountain town is so popular among hikers that it has been given the title “Trekking Capital of Argentina.” Below, I’ll provide bits of logistical information I’ve gleaned from spending two summers in El Chaltén, including beta (as we climbers say) on transportation, lodging, weather, and gear.

Only highly experienced climbers should attempt to climb in the Chaltén massif. This range is unlike anything in the lower 48—given the weather, loose rock, and glaciated terrain, it is not to be taken lightly. The advent of weather forecasting and changes in weather trends have made the area accessible to the masses; as a result, these mountains have seen an increase in accidents in recent years. Let’s put it this way: if you are reading this article to gather information on climbing in the Chaltén massif, you probably aren’t ready. Hone your skills, take a few trips to the Bugaboos, the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, Alaska, or the North Cascades—and then revisit your Patagonian dreams..jpg)

For the most direct travel to El Chaltén from the States, fly to Buenos Aires and continue on a domestic flight to El Calafate. We recommend you purchase this entire ticket as one itinerary (although you’ll likely have to switch airports in Buenos Aires), as it will make life easier in the event that you need to make changes. El Calafate serves as a bit of a hub for southern Patagonia, connecting the area by bus and plane to popular tourist towns such as Mendoza, Bariloche, Ushuaia, and Puerto Natales. Multiple bus companies operate 3 to 4 hour shuttles several times daily between Calafate and Chaltén. Alternatively, if you have a group of four, you can take a private taxi for about the same cost..jpg)

A rental car is not necessary for your stay in Chaltén. It takes less than 15 minutes to walk from one side of town to the other, and the trailheads are just minutes from hotels and restaurants. The trail to the Torre Valley leaves from the top of the hill (follow Avenida José Antonio Rojo up the black metal staircase and turn left), marked by a sign on Calle Riquelme. Another trail begins from the parking lot at the north end of Avenida San Martín, heading to the east faces in the Fitz Roy Massif and landmarks such as Laguna Capri, Laguna De Los Tres, and Campamento Poincenot. To reach Piedra del Fraile or Lago del Desierto, hire a taxi or book a shuttle from town.

.jpg) It has become increasingly convenient to book rooms in Chaltén, with many of the hotels now listing on online platforms like booking.com. And if you arrive in town without reservations, any of the numerous hostels or campgrounds likely will be able to accommodate you. For those hoping to stay a month or longer, Airbnb is a good place to begin an apartment search. For longer-term stays, also check out La Base, Inlandsis, and La Avenida Apartamentos.

It has become increasingly convenient to book rooms in Chaltén, with many of the hotels now listing on online platforms like booking.com. And if you arrive in town without reservations, any of the numerous hostels or campgrounds likely will be able to accommodate you. For those hoping to stay a month or longer, Airbnb is a good place to begin an apartment search. For longer-term stays, also check out La Base, Inlandsis, and La Avenida Apartamentos.

There’s only one guidebook worth buying for climbing in the mountains outside of El Chaltén: Patagonia Vertical: Chaltén Massif by Rolando Garibotti and Dörte Pietron. Even for non-climbers, this book is a masterpiece, full of beautiful photos and intriguing history on the range. We also recommend you pick up a trail map, available at any number of shops in town.

While we’re on the topic of books, I can’t help but put in a plug for Kelly Cordes’ book, The Tower. This read is ostensibly about the history of Cerro Torre, but no other piece of writing (in my opinion) presents such an intimate look at the climbing culture of El Chaltén. If you found the story above at all interesting, you won’t be able to put The Tower down.

One the side of Rolando (Rolo) Garibotti and Dörte Pietron’s small log cabin in Chaltén hangs a sign that reads, “World’s Worst Weather.” The couple’s house is climbers’ undisputed watering hole for information on weather. While the conditions haven’t necessarily changed leaps and bounds in the past decade (there were a few notable years in the early 2010s with uncharacteristically calm summers), weather forecasting certainly has. Before heading to the mountains, climbers read complex meteograms and weather maps for pinpointed and hour-by-hour forecasting. Every day—actually multiple times a day—I consulted both the NOAA Meteogram and Meteoblue’s Multimodel to determine when I would head to the mountains and what objectives would be best to attempt. Hikers who are sticking to the trails can generally get by with more typical weather forecasts, but will want to pay specific attention to the predicted wind speeds.

Your gear needs in Chaltén will depend heavily on your activity of choice. Climbers often arrive in town with three or four duffels stuffed with a storage shed worth of gear and food. Hikers, on the other hand, can get by with a lot less. If you’re planning on camping in town or on the trail, make sure that you have a sturdy, three-season tent that is well-built to handle heavy winds. You’ll also be grateful to have a wind-resistant stove like the MSR WindBurner (see more of our recommendations for stoves here). Both white gas and isobutene/propane mix are available for purchase in town. Park rangers will tell you that river and lake water comes straight from the glacier and is therefore safe to drink, but we recommend you use your judgment. Make sure to choose clear, running water sources rather than those that are silty and still, and bring chemical tablets or a lightweight filter for water treatment.

Even though summer temperatures are relatively fair, the wind is strong enough to cause a chill. Make sure you have a highly wind-resistant hardshell or rain jacket, breathable and wind-resistant pants, and a comfortable and wicking baselayer. In terms of footwear, we recommend a comfortable and lightweight pair of trail shoes (boots will be overkill for most applications) or even trail runners. And if you forget anything, there are several gear shops in town that both sell and rent all kinds of outdoor equipment.

Grocery stores in El Chaltén offer an assortment of cheeses and meats, crackers, chocolate, and fruit. Almazén, in particular, is a wonderful place to shop for nuts and dried fruits, and Curcuma is a must-try—their vegan and gluten-free hummus wraps are perfect for the trail. If you’re attached to energy bars or dehydrated meals, know that these will be difficult to find in Argentina. That said, I highly recommend Mantecol, a peanut butter nougat that’s an Argentine specialty. This candy bar-slash-energy bar is one of the only ways to consume peanut butter while in the country, and is an excellent, calorie-dense choice for the trail.